I learned quite a lot from the 2-Way Catalina experience.

- 2-Ways are physically hard. Really hard, and harder than I had prepared for. While I was not a ‘spent force’ at the end of the first leg, I had just completed a 20-mile channel swim, so my body was at the very least ‘compromised’. I was actually physically OK till about 24 hours in, once I had got over the massive wobble at 15-16 hours, but then things got very hard indeed. I had never before been in the situation where my body actually refused to do what I wanted it to do. The pain from my left shoulder just ordered my brain to stop. Could I have gone longer and harder ‘if my life had depended on it’? Probably, but that isn’t the answer. If I were ever to contemplate a swim of this magnitude again, I would need to go and get my stroke corrected. Apparently the guys on the boat had some fun looking at my stroke (let’s face it – they had plenty of time to do so), and found it ‘not without opportunity for improvement’. Am I too old a dog to learn new tricks? Let us see…….

- If you get common injuries and sore bits in training, they might show up when you do a 2-way, or they might not. My common places for trouble are triceps, lats, left ribcage, hip flexors, deltoids, lower back. The ribcage hurt between 20-24 hours then went away. The deltoids (tops of shoulders down the upper arm) were what slowed me in the end. Everything else was fine. Didn’t even hurt the in the days following. All very surprising.

- Salt mouth is an absolute pain in the a**e. it got steadily worse as the swim went on, and it took a week for me to be able to spit properly or eat without pain. It was the most troublesome thing by far in my recovery.

- 2-Ways are mentally hard. My mind went way before my body did, possibly tipped over the edge by hitting a wall when my available glycogen ran out. It took me a good hour to get through it, and only with some tough words and messages from the boat. I thought I had the computer programmed properly before I started. I had prepared myself for a swim of 28 hours. That was my ‘par score’ and that was precisely what I ended up with. I think I got downhearted by the slow progress I was making back through the cross currents on the Catalina side. I allowed that to mess with my mind. Inappropriate extrapolations screwed me up. Which leads me neatly on to…..

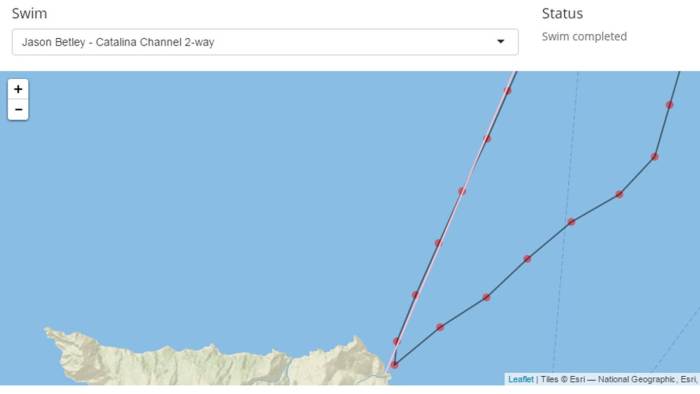

- Knowing where I was – probably a bad thing. My decision to be told how far I had gone after every hour was, in retrospect, not a great one. I had focused only on the good part of this knowledge, being able to do mental maths and tick off the swim, kilometre by kilometre, and to revel in the progress. I had not planned enough mentally on how to deal with the effect of ‘bad news’ on swim progression. I had concentrated on the positive effect knowledge about how far I had gone in the 12-hour Dover swim. This was temporal knowledge though, and very defined. 8 Hours was 2/3rds of the way to the finish, whatever changes remained in conditions, swim speed, state of mind etc. In a swim like this, time is elastic, and it was elastic (and unknowable) time that got me into trouble.

- Catalina is a harder swim in some ways than I had given it credit for. The cross currents rubbed off a lot of my speed, and some of the least helpful currents came right at the end in the last 3-4 miles. It was also an easier swim in some ways than it might have been. The water was warm, conditions were on average much less challenging than my English Channel, and there was nothing too scary or painful.

- I was not a very pleasant person to be around for large parts of the swim. I would have preferred to have been even-tempered, sunny and a joy to be around for the duration. This was sadly not the case. I was grumpy, sarcastic and moany for most of the second half, which I know wasn’t easy for those on the boat. While I know that this sort of behaviour is by no means uncommon, please accept my apologies.

- I have a champion stomach. I chugged away on approximately 20 litres of feed, containing somewhere in the region of 1.5 kg of maltodextrin powder. Add in a few milkshakes, a couple of tins of peach slices, some jelly babies, and a couple of bananas, plus painkillers, and that was my diet. I wasn’t sick once, nor was I bloated apart from a little in the first few hours, while my nerves were settling down.

- Taking myself to the point where I was ready to break, and to keep going, was a valuable life experience. Triumphing over some adversity was a useful affirmation of what I am capable of, physically and mentally. I am proud of finishing.

- I can only imagine how hard an English Channel 2-Way would be, especially for swimmers who are not especially fast like me. I think it would be even harder than the Catalina 2-way, simply because you are likely to be in the water for even longer. Wendy Trehiou landed a 40 hour English Channel 2-way a couple of years back. Words almost fail me. And remember there are people out there who contemplate and take on 3-ways. Chloe McArdel became only the 4th person in history to achieve the EC 3-way, earlier this summer.

- This is a reminder that there are always ‘greater and lesser persons than yourself’ – in everything in life. And guess what? It doesn’t matter. Do your best, and revel in your achievements. I am happy that I have learned quite well the limits of what I can do swimming-wise. If that swim had been much further, or colder, or windier – I would have been in deep trouble.

- One pint plastic milk cartons make great feed containers.

And now to some thank you’s.

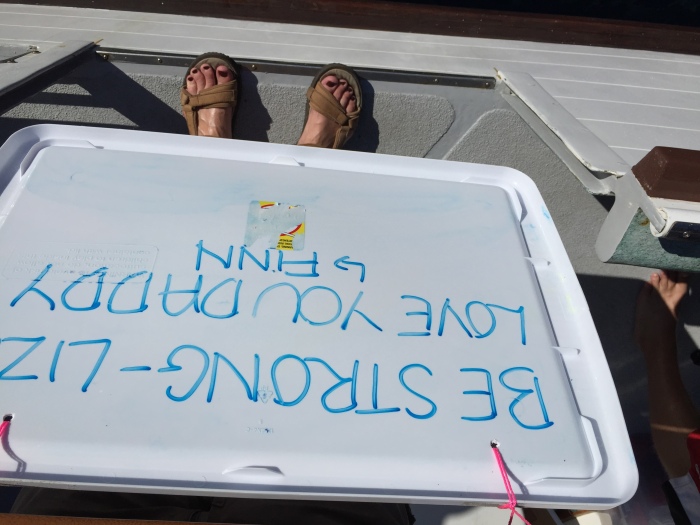

Firstly to my crew. I have written before about how important it is to ‘feel the love’ from the boat. I certainly did feel that. Helen was there for damn near the whole swim, watching over me. It must have been super hard for her to see me struggling, her pulling out all the stops, turning all the dials, to improve things, but still helpless at the end of the day. A massive ask in retrospect, for which I owe you a huge debt of gratitude. Thank you Helen.

Bojan had never crewed on a Channel Boat before but was, by all reports, an absolute champ.

Dan and Kevin kayaked beautifully, and provided great words of encouragement at all times. They were also there with me throughout training in the last year, whenever I visited La Jolla.

I was incredibly lucky to have such an amazing and empathic crew, each with at least one Channel Crossing to their names, to help me over and back.

The Observers. Don, Bob, Sakina. Thank you for volunteering for the sport, and being there for me. Please accept my apologies for being so slow, especially when the end seemed so close.

The crew, especially John and Scott who piloted so expertly. They were also incredibly patient. It was hard enough in the water being a slowcoach at the end of the swim, without being made to feel like one, by feeling impatience from the boat. I really was doing my best 🙂

To Dylan, Emmeli and the boys who put Helen and I up in their rental apartment overlooking the ocean. This was great in itself, but their warmth and interest in what we were doing was quite touching. Sitting in the hot tub drinking champagne the evening after the swim was really living the dream!

To everyone else back in the UK who has supported me in training. The beach crew, other swimmers with their words of encouragement and belief that I could do it.